Lt. N., one of three women to finish the IAF’s 180th pilots course, is the third generation of her family to fly in the Israeli Air Force.

Hatzerim Air Force Base, late June: Jumpsuited new graduates of the 180th IAF pilots course are standing at attention in front of a row of planes from the 102nd Squadron.

Four pairs of pilots and navigators head out to the Lavie planes, including Lt. N, a navigator and one of the only three women to graduate in her class. Ordinarily, N. would arrive carrying her helmet and put it on while standing next to the plane. Now, in the shadow of coronavirus, everyone arrives protected.

N. runs her hand over the plane to make sure everything is all right, that there are no cracks on the wings, no bird stuck in the engine. Later, she will stand squarely in front of the aircraft to make sure it’s balanced. It’s a routine check, and a private moment with her aircraft.

“It’s my little ceremony,” N. explains later, with a bashful smile. “A moment where I connect to the plane. I like to look at it and ask it to be good to me, for there not to be any problems. The same way some people believe that you have to enter a new house on the right foot.”

N. climbs up to the rear seat of the Lavie. It’s a fairly new Italian aircraft, only in use in Israel for six years, and for training. The engines start, the wheels begin to move, and in a moment, the plane shoots forward on the runway and disappears into the sky. Three others follow.

Less than half an hour later, N. is back on the ground, rushing to study her flight in the squadron room. After every flight, performance is evaluated, and pilots and navigators learn what they can improve. N. has been flying on the Lavie for the past year and a half, after dozens of hours in smaller training aircraft.

Despite being one of only 59 women to graduate the pilots course since the inception of the Israeli Air Force, N. stays modest.

N. was near the end of her compulsory service when she made it into the course, and at age 24, she was one of the older cadets. Her eyes are clear and pretty, and she speaks rapidly and with confidence. She already has a BA in politics and government.

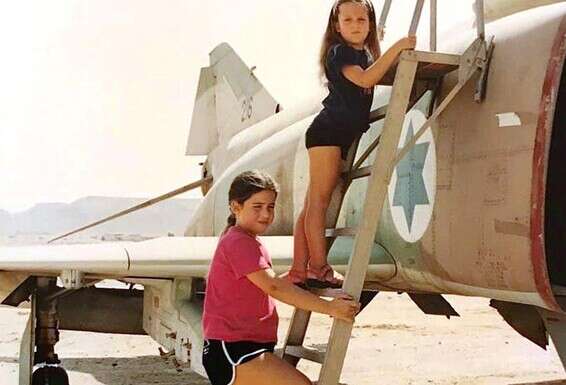

N. comes from a long line of IAF personnel. Her grandfather, Brig. Gen. (ret.) Amichai Shmueli, 84, was commander of the 117th Squadron during the 1967 Six-Day War and commander of the Hatzerim Air Force Base during the Yom Kippur War of 1973. Two of his three sons served as IAF pilots. N.’s maternal uncle was also a pilot.

Her father, Lt. Col. Y., 55, was a combat pilot who flew on Kfir and Skyhawk aircraft. He commanded a squadron out of Uvda, and seven years ago became a flight instructor in the reserves. Since 2006, he has been a civilian pilot for El Al (he is currently furloughed). Her mother, a scientist, did her military service as an operations clerk with the 102nd Squadron.

N.’s younger sister teaches on flight simulators at Hatzerim. Sometimes they run into each other on the base.

N. was born at Hatzerim, where her family had quarters, and when she was five they moved to Uvda Base, and from there to Reut. In high school, she specialized in physics and theater. In 2014, when she enlisted in the military, she completed a course to train pilots on simulators, and then served as an instructor at Palmachim Base, which required her to sign on for extended service.

“I never dreamed of being a pilot or anything,” N. says, smiling. “When I enlisted, they didn’t invite me to join the pilots course, and I didn’t ask. The other jobs seemed interesting and challenging enough.”

She has trained hundreds of air personnel on simulators, but only in her third and final year did she start to see the attraction of flying.

“Suddenly, I started getting more interested in what the fliers were doing and wanted to move onto that. The desire to get into the course grew from there,” she says.

Her parents didn’t push her in that direction.

“We weren’t wild about the idea, because we know the dangers of that path,” says her father, Y. “We know the difficulties of the course. The cadets are always under pressure, and we knew that we would be tense at every stage of exams and cuts. Every few months, everyone is ‘grilled’ and they’re always tested on their performance and abilities. It’s enormous pressure.

“We told her what we were told as children: ‘If you want it, go for it.’ We knew she would. She always had big aspirations and great abilities,” her father adds.

N. was approved to try out for the course. She passed the requisite medical, psychological, and personality tests.

“Suddenly, I wasn’t 100% sure it was what I wanted to do. I took a few days to decide if I wanted to start the course [that] July, or be discharged. I didn’t have big plans for life after my discharge, there was nothing specific I wanted to study or any big trip I had planned. In the end, I said that if I regretted it, I could be discharged at the early stage of the course. Later, you have to sign on for seven years of career service.”

She arrived at the pre-course trials and was happy to hear her name called out as having made the cut. Her cell phone battery was dead; she borrowed someone else’s mobile and called her parents, who told her they were proud.

Her course began on July 13, 2017, three days after her original discharge date.

“For others, it was their first encounter with the army. For me, it was more service … From the rank of staff sergeant, I went back to six months of basic training, with schedules and sleeping in tents,” she says. “But I enjoyed it.”

The pilots course is split into several stages. The first two comprise a year of ground training that includes basic training and theory, fitness, leadership, etc. Then cadets are divided into various tracks, such as combat, transport, etc. This is followed by a year of academic study and six months of advanced training, when they actually fly.

“The things you go through in the course, with everyone else, make everyone good friends. There was one time we had to navigate in pairs. I was paired with K., and each one was responsible for one part of the navigation. We started to get lost, we couldn’t find our way, and we were running short on time. We realized we had failed, and the commanders told us to open our maps, which is like when a driving instructor hits the brakes for you.

“In the end, we went 22 km. without knowing where we were going. We had a good few hours to get to know each other, to talk.”

N. did not pass her first test on the Efroni [T6 Texan II] training aircraft. “It was really hard for me. Not just because it was a test I failed, but because it was a test I was supposed to fly on my own after passing. I was disappointed in myself, frustrated because I knew I could perform well, but hadn’t.”

“Two days later, I was tested again, this time with a million percent motivation to succeed, and I passed. I flew for half an hour with the examiner, and then I dropped him off and flew again on my own. Just me and the plane, alone in the sky.

“Flying is insane,” she says, her hand resting on her heart. “It’s an amazing sensation, a sensation of power, with a lot of responsibility. The air force gives you a plane, alone, and you need to take off and fly and land on your own. It’s all up to you, because no one else will land the plane,” she says.

The mid-course evaluation committees assigned N. to the combat track as a pilot. A few weeks later, they determined that she was better fit to serve as a combat navigator.

When asked if she was disappointed at the reassignment, N. says, “No, the opposite. I was happy I was still in the course. I thought they were giving me a chance to serve in a role I’d be good at. I didn’t come in with the dream of being a pilot, I didn’t have a specific job in mind.”

As part of their training, cadet navigators fly with pilots who completed the course six months before them.

“So we fly with friends from the course before us. It’s an amazing feeling. On one hand, you’re flying with someone you know and you’re comfortable with, and they’re about your age. On the other hand, you have to maintain professionalism and stay responsible.”

Shortly after her first solo flight, cadets’ families were allowed to visit. N.’s parents, sister, and even grandad Amichai came to the base where they had spent considerable time. The cadets still flew their training flights, with their parents watching from the side of the runway.

Amichai, who has seen plenty of cadets flying planes, was moved.

“It’s unbelievable. Suddenly I see this girl, who would cry at nursery school, climb up into the plane and fly it,” her grandfather says.

Y., the proud father, adds: “Anyone who knows the profession knows that she’s sweating inside. She’s not flying abroad for a vacation. When she’s in the plane, it’s hard work, and it was moving and captivating to see her doing it.”

While Y. still has friends at the base, N. says no one has gone easy on her.

“There are certain instructors I didn’t fly with because they know my dad. It wouldn’t be professional to fly with someone who served with your father. I’m not the only one with a family history in the air force, and everyone knows that we stay professional and there’s no favoritism for relatives.”

Y. says, “She wasn’t accepted to the course because of me, just like my brothers and I weren’t accepted because of our father. She succeeded because of her own talents, which are better than mine, because she got them from her mother.”

N. likes the fact that her parents understand her world, “because when I come home, I can tell them about a flight or about combat air training, and both my parents will understand what I’m talking about. Sometimes my dad will say, ‘You could have approached it like this,’ and demonstrate with his hands, and I show him another way of doing it.

“On the other hand, my parents were in the air force a long time ago, and now it’s different. So I mostly share experiences, and talk to them less about flight systems and stuff.”

A total of 250 cadets started the course with N. She was one of only 40 to graduate – 37 men and three women.

“The demands on the girls are almost identical to those on the boys. Other than the physical standards in the first year, where we lift lower weights to prevent injuries. Aside from that, no one cut us any slack. I was happy there were other girls, we were good friends. The air force needs high-quality personnel, and it doesn’t matter whether they’re men or women,” she says.

N. says that most women don’t think they can complete the pilots course, and calls that “a shame.”

“Girls should come and try out, even if they think it’s hard, even if they think they won’t succeed. It’s better to try, and if worst comes to worst, fail, than not take advantage of a chance to fly.

“True, there are a lot of amazing jobs for women in the army, but being on the front line is insane, and pilots are on the front line. So I suggest that every woman who is offered the chance take it,” she urges.

Amichai says, “If today there are women directors of hospitals, female professors in research institutes, there’s no reason why there shouldn’t be women pilots. Girls can at least try the course. It’s tough, physically, too, but if they have high motivation, young women can do it just like a guy can.”

Is N. eager to start flying actual operations?

“Very impatient,” she says with a grin. “I really want to start taking duty shifts.”

“I feel very confident in the place, but for now I’m still at the learning stage. I’m taking it step by step. The way I see it, this is the stage to practice and be the best I can at what I do. It will take time before I can fly on operations.”