How Jews Redesigned the Fashion Business

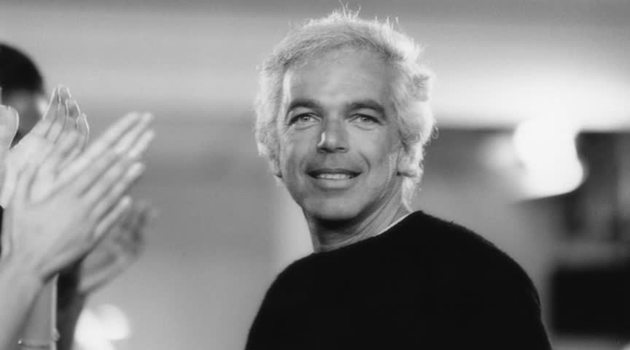

To celebrate his 40th anniversary in the fashion business, Ralph Lauren staged an elaborate runway show and black-tie party in New York’s Central Park Conservatory Garden. Arranged on the themes of ‘A Day at the Races,’ the event drew a gaggle of celebrities from Robert De Niro and Martha Stewart to Vera Wang and Diane Sawyer. Spectacular jackets of black-and-white stripes worn over tight-fitting long gowns with black-and-white patterns marched down the runway, interspersed with evening gowns of vibrant pastels and menswear done for women in black and white with the signature Annie Hall ties framed by exuberant yellow vests.

Harold Koda, curator at the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, marveled at Ralph Lauren’s ability to deliver a rendition of the privileged American life that was so convincing it appeared to be a self-portrait of the nation. “Like a Henry James character, he is the last true idealist about America’s imagination of itself,” said Koda. “That makes him the greatest ambassador of American style.”

Ralph Lauren is ubiquitous in fashion, head of a powerful $13.5 billion global empire that designs all of its products – from sportswear to fragrances to home furnishings and even paint – with an aura of casual American comfort and upper crust British class. In keeping with the Polo image, he has perfected his persona as a charter member of the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant establishment. He’s a car enthusiast who maintains a world-class collection of rare automobiles, a patriot who helped the Smithsonian restore the flag that inspired the Star Spangled Banner and suited up America’s athletes for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. But unlike his persona as a charter member of the WASP establishment, he is also a son of Israel.

Ralph Rueben (cq) Lifshitz was born in the Bronx to Ashkenazi immigrants from Belarus who sent their four children to Jewish day school. His father Frank Lifshitz was a house painter who longed to be an artist, and sometimes used the name Frank Lauren on paintings in hopes of capturing a broader market.1 Green-eyed Frieda Lifshitz, who insisted her four children go to the Yeshiva, hoped they would bring her “Jewish nachas.”2 But Ralph, the youngest, had other ideas. A basketball enthusiast who shared a bedroom with two other brothers, Lauren early developed a fascination for clothes with a button-down style. While other kids in his 1950s school were wearing motorcycle jackets, he saved money from after-school jobs to buy oxford shirts, crew neck sweaters, and white high-top sneakers.3 When he couldn’t find clothes to match his instincts, he designed his own.4 Encouraged by his father, who appreciated his sense of color and texture, Ralph Lauren was the first breakout design star of the post-war era, the pioneer who first understood the power of branding and the global hunger for assimilation.

His success was a template for a generation of Jewish designers who put American style on the fashion map in the years after World War II. Freed from Paris’ lock on style, empowered by a baby boom generation of consumers, Anne Klein, Judith Leiber, Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein, Diane von Furstenberg, Donna Karan, Kenneth Cole and Michael Kors burst on the scene in the 1960s and 1970s, remaking fashion in the image of their times. After them came a new generation, Marc Jacobs, Isaac Mizrahi, Zac Posen, who in the 1990s and 2000s, helped democratize luxury, all but ending the business of haute couture.

Most of the designers see little connection between their religious roots and their fashion inspirations. But all of them owe something to the Jews who came before, ancestors who never saw the inside of an English country estate or watched a parade of rail-thin beauties sashay down the runway. Generations of czars and emperors in Europe over the centuries had stripped Jews of their connection to the land, restricting them to work as tailors or peddlers or bankers. Their very existence depended on their acumen at reading the needs and desires of the larger culture. That antenna for what would play, an accident of historic discrimination, was the distinct advantage that smoothed their journey in fashion from worker bee to trendsetter.

First came the Sephardic, the Mediterranean Jews who fled the Spanish Inquisition by way of the Netherlands and Brazil. Two dozen eventually landed in New Amsterdam (later renamed New York) to form colonial America’s tiny Jewish community. As the community grew, they settled in Newport, Rhode Island and Charleston, South Carolina, softened the religious orthodoxy of their fathers, and fought in the Revolutionary War.

Then came the Ashkenazi, the European Jews fleeing persecution and political disillusionment in Germany in the heart of the 19th Century, numbering 250,000 by the 1880 census that counted 50 million Americans. Educated and enterprising, seeking freedom of opportunity, the German-speaking Jews moved West with the country, chasing the frontier South and West, fighting on both sides of the Civil War.

But few migrations in history matched the Jewish flight from Eastern Europe after the assassination of Russian Czar Alexander II in 1881. A reformer who allowed Jews to attend university and practice their trades, a visionary who built the railroads and drafted plans for a democratic Duma, Alexander kept the winds of revolution at his back. With his death, his son’s repressive policies forced Jews into one large ghetto stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. This Pale of Settlement reduced the Jews in Warsaw, Odessa, Kiev, Vilna and other cities to endemic poverty and subjected them to violent crackdowns. By the time World War I closed the gates, more than two million Jews had poured into America. At the peak they streamed into Ellis Island at a rate of 18,000 a month, with ferries running to New York and New Jersey twenty-four hours a day. Speaking Yiddish and clinging to their communities, they settled for the most part in the cities, and many of them gravitated toward the needle trades.

For once, timing was on their side. Before the Civil War, most Americans wore hand-sewn clothes, made at home. But in the mid-1800s, several inventors, including Isaac Singer, won patents for a sewing machine. Suddenly, mass production of clothes in standardized sizes was within grasp. Dry goods stores – many of them owned by German Jewish immigrants – rushed to capitalize on the opportunity. The country was on the move, expanding South and West in a migration of people and commerce that gave new definition to the term pioneer and new weight to the gods of convenience. By 1890, most Americans were buying their clothes ready-made in shops or ordering them from the Sears Catalogue.5 And by the turn of the century, 60% of all the Jews employed in New York made their living in the garment industry.6 It was one of those paradigm-shifting moments in history.

As Malcolm Gladwell has noted, the Jewish immigrants had the skills to match the market’s needs. “To come to New York City in the 1890s with a background in dressmaking or sewing or schwittwaren handlung (piece goods) was a stroke of extraordinary good fortune,” he wrote in Outliers: The Story of Success. “It was like showing up in Silicon Valley in 1986 with ten thousand hours of computer programming already under your belt.”

Beyond the talents of their needles, the accident of historic discrimination in Europe gave Jewish immigrants an unexpected advantage in America’s melting pot, a way not just to earn a living but to re-invent themselves. Here was a country where image was king, where even if you spoke no English you could look the part, where a newcomer could go from Yid to Yankee just by changing clothes. “I was forever watching and striving to imitate the dress and the ways of the well-bred American merchants,” said one man who arrived from Eastern Europe, where his wardrobe featured coarse pants and rough textured shirts. “A whole book could be written on the influence of a starched collar and a necktie on a man who was brought up as I was.”

The 501 blue jean was the first Jewish success story of fashion.

The year was in 1870 and Latvian-born Jacob (Youphes) Davis, had tried his hand without success at panning for gold, selling tobacco and pork, and running a brewery. Now, married with six children, he was back in his tailor shop on Virginia Avenue in downtown Reno. A woman came in and asked him to design a pair of work pants for her husband, a large man who kept splitting his seams. After accepting the $3 commission, Davis pondered the problem. He began work using a heavy duck twill material purchased from the Levi Strauss general store in San Francisco. As he finished, the bearded tailor spotted on his workbench the copper rivets he used for cattle drivers’ horse blanket straps. So he added them to the seams to make them more secure. Later, during a patent infringement case, he testified about his invention.

“So when the pants were done – the rivets were lying on the tables – and the thought struck me to fashion the pockets with rivets. I had never thought of it before,” Davis told the court.7

In that flicker of inspiration, he invented the quintessential American garment, jeans. Word traveled up and down the railroad line about the sturdy work pants. In the next 18 months, Davis sold more than 200 pairs to miners, surveyors and teamsters. Overwhelmed by the demand, worried about imitators, without the money to apply for a patent, Davis wrote to his San Francisco supplier. He included samples of the pants he had made in both white twill and blue denim, paid a past due bill of $350, and asked Levi Strauss to become his partner.

Loeb Strauss was also an immigrant, arriving in New York in 1847 at the age of 18 from the Bavarian region of Germany. The youngest in his family to make the journey, Strauss worked in his family general store in New York, learning the business from his older brothers. But when the Gold Rush seized the country’s imagination, offering to all those in rags the promise of riches, Strauss changed his first name to Levi, became an American citizen and set off for California. He never intended to pan for gold himself, only to outfit the miners. And so he did, opening a general store in San Francisco, selling material to tailors like Davis and supplies to retailers up and down the West Coast. When he read Davis’ letter, Strauss had already tried his own hand at designing sturdy brown work pants, and leapt at the chance to patent a winning formula. Together, he and Davis won their first patent for the pants in 1873. A few years later, the company started giving lot numbers to its merchandise, assigning famous lot “501” to the pants with the rivets. By then, the miners were calling the pants “Levi’s,” so the company patented that name too. The two produced jeans together until 1907, when Davis sold his interest to his partner, missing out on generations of potential wealth for his descendants. But by then the tailor from Riga was listed in the San Francisco city directory by a title that would have pleased him: “capitalist.”

He was not alone. Within a few years of their arrival, Jewish immigrants dominated the garment industry.

The Davis-Strauss partnership thrived in part because the sewing machine meant production of more clothes at far greater speed than ever before. The machine patented by Isaac Singer had already revolutionized military uniforms – during the Civil War both the Union and the Confederacy contracted out for clothing. Those contracts helped launch a tradition of Jewish family-run businesses in clothing manufacturing, including the four Fechheimer brothers of Cincinnati, whose father and grandfather had been clothing peddlers in Germany.

Rabbi Moses Phillips, an immigrant from Poland, began sewing flannel shirts sewn by his wife Endel and selling them from pushcarts to coal miners in Pottsville, Pennsylvania in 1881. As the business grew, so did his sophistication. Before long, M. Phillips & Son became the first shirt-maker to advertise in the Saturday Evening Post. Later, the father of eight joined forces with a Dutch immigrant, John Van Heusen, to form the world’s largest shirt company. And in 1919 the combined company won a patent for a soft-folding collar that revolutionized men’s shirts. Two years later they were on Wall Street, trading publicly on the New York Stock Exchange.

The early inventors understood what other immigrants sensed too, that in America clothes were an elixir – a way to earn a living and a path to re-invention. “Based in urban centers and pushed by history toward entrepreneurship, Jews found fashion one of the fields open to them,” said Valerie Steele, historian at the Fashion Institute of Technology. Here was a country too where image was king, where a man could become an American just by changing clothes. “I had a new navy blue cashmere dress, the first dress I have ever had that was not home-made and too large for me,” wrote Rose Cohen, in Out of the Shadows, a 1918 book about her life as an immigrant from Eastern Europe. “It cost me a week’s wages and many tears but it was worth it.”

From the beginning, the connective tissue of Jewish history in the rag trade was family. The thread that stretches from Levi Strauss to Isaac Mizrahi, from union laborers to runway designers, is made of mishpucha. For all the glitter of the runway, the rag trade is a family business, and Jews were soon hiring Jews to produce and sometimes even design the clothes of the 20th Century.

“This business, the fashion industry, is truly a family business,” said Andrew Rosen, founder of Theory and now CEO of Helmut Lang. “This is not just about making clothes to fill up racks in stores.” Rosen should know. His grandfather Arthur founded Puritan Fashions in 1910, his father Carl was a leading Seventh Avenue executive and Puritan produced the designer jeans that helped make Calvin Klein a fashion icon. “It’s about relationships, about community, about threading one generation to the next.”8

As the business grew, so did the extended family. Jews were involved in every aspect of clothing – from the supply end to the retail world, from the sweatshops and manufacturing to the department stores and the advertising. Corporate America still maintained a strong glass ceiling – the Gentlemen’s Agreement barred entry into fields like medicine and the law – but in the schmatte business, the only ceiling was creativity and sweat equity, savvy and timing. “Every Bar Mitzvah became a garment industry convention,” said Gabriel Goldstein, curator of a Yeshiva University exhibit called “A Perfect Fit: The Garment Industry and American Jewry, 1860-1960,” and a leading expert in the field. “The calendar was marked by the High Holidays and Fashion Week.”

By the 1930s, a few breakout stars emerged.

Adrian (born Adrian Greenberg) became the first major costume designer in Hollywood, helping a generation of Jewish immigrant moguls define glamour. A favorite of the stars, Adrian set new standards in movie creativity by dressing the characters in the 1939 classic The Wizard of Oz, including the film’s signature red-sequined ruby slippers. Macys copied one of his designs for Joan Crawford – worn in a 1932 movie called Letty Lynton – and sold a half million dresses. Adrian’s designs in the 1939 film The Women were so breathtaking that while the movie was shot in black and white, MGM used Technicolor for a 10-minute fashion parade featuring his work.

As Adrian was designing for Greta Garbo and Norma Shearer in Hollywood, a few Jewish designers in New York were also gaining national fame.

Hattie Carnegie was born in Austria as Henrietta Kanangeiser and decided in America to take the name of the country’s most famous industrialist. From her own boutique, Hattie designed colorful dresses and artful jewelry – now much sought out by collectors — for actresses Crawford and Tallulah Bankhead and political figures Clare Booth Luce and the Duchess of Windsor. She also employed a cadre of seamstresses, like Calvin Klein’s grandmother Molly, who taught the future design star to sew.9

Sally Milgrim was a favorite of Eleanor Roosevelt, who hired her to design the light blue gown worn she wore to her husband’s first Inaugural ball in 1933. Known for the quality of her clothes and accessories at a time when most ready-to-wear items were anything but, she won contracts from actresses Ethel Merman and Mary Pickford.

Austrian-born Nettie Rosenstein, dubbed by Life Magazine as “among the handful of American dress designers who compete successfully with Paris,” designed both of Mamie Eisenhower’s Inaugural Gowns.10 In an era when department stores insisted on putting their label on the clothes, Rosenstein convinced Bergdorf Goodman and I. Magnin to carry her line under her own label.

“Certainly until 1930 you didn’t hear the names of designers,” said the FIT’s Steele. “You heard names in Europe – Chanel and Worth – but in America, departments stores like Wannamaker’s and Garfinckel’s” controlled the label. “As late as the 1960s,” she added, “most department stories deliberately kept designers in the background.”

And then there was Mollie Parnis, who with her husband Leon Livingston (nee Levinson) opened a business in 1933, at the height of the Depression. Though she could not cut, sew or draw, Mollie Parnis Livingston had what one observer called “an architect’s eye for proportion,” offering designs geared to flatter women over 30. Her influence lasted beyond World War II, and reached notoriety in 1955 when First Lady Mamie Eisenhower arrived at Washington reception wearing a Mollie Parnis Livingston blue and green taffeta shirtwaist only to discover another guest wearing the same dress.

For all the early fame of the pre-war designers, it was really the design aftermath of World War II that served as a seminal divide in fashion history.

In Germany before the war, Jewish families operated top of the line department stores, part of the thread of Jews serving the needs of the Gentile society. When Hitler came to power, the terrible shards of Kristallnacht (German for “a night of broken glass,”) smashed the windows of synagogues, homes and more than 7,500 Jewish shops. One was Nathan Israel’s Department Store, a Berlin institution founded in 1815.11 Ironically, no one understood the loss to Germany’s cultural and artistic base better than Magda Goebbels, the fashion conscious wife of chief Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels and a woman so dedicated to the Third Reich that as the allies were closing in on Berlin, she is said to have killed her six children in Hitler’s bunker before arranging her own death. “Along with the Jews,” she said, “elegance disappeared from Berlin.”12

In Paris, French culture suffered too. Some couturiers designed for wives of German officers and for black marketers who sold butter, eggs and cheese in the back door and left with opulent designs out the front.13 Others closed their houses. One was arrested for doing her entire collection in France’s tricolors. All of their work was shuttered from view. Where once American manufacturers had copied French design for the mass market, now they had to reinvent themselves, retooling for a coming post-war shift in power. “With the black out of Paris, our own designers will … dictate style,” the New York Sun predicted cheerfully, and prematurely.

Against the odds, Paris came back, though not without struggle. Wartime rationing in the allied countries had been severe. Women in Britain were encouraged not to buy new clothes, to “make do and mend.” Stanley Marcus, scion of the Neiman-Marcus Department Store in Dallas, went to Washington to work for the War Production Board, freezing the silhouette so Americans would not buy new clothes, promulgating and publicizing a regulation (the infamous L-85) that limited the amount of fabric in those new clothes they did buy. So when fashion British and American fashion writers got their first look at French wartime designs, they revolted.

“While we are wearing rayon,” lamented Vogue Magazine, usually a loyal cheerleader for Paris, “the Frenchwoman is wearing yards of silk.”14 Truth was that most women in France during the war were freezing, wearing thread-bear clothes and culottes that allowed them to bicycle when they could no longer afford petrol for cars. But the allied fashion writers were outraged, and Paris blinked in their anger. Word spread Coco Chanel — a fashion icon who invented the knit suit for day and the little black dress for evening, and the classic perfume Chanel No. 5 – had spent the war years living at the Ritz with a Nazi officer.15 With criticism mounting, trade association head Lucien Lelong explained that French excesses in material were meant to rob Berlin of funds needed for the war effort. Every yard spent in fashion, he said, hurt the Third Reich’s bottom line.

On the defensive, Paris designed its own rescue, creating a spectacular exhibit of hundreds of dolls, standing 27.5 inches high and dressed by the city’s top couturiers. The Theatre de la Mode dolls traveled the world to rave reviews, reminding audiences of the marvel of French artistry. Giving notice that Paris was back, Christian Dior sparked the first rage in post-war design with his New Look of cinched waists and voluminous skirts. Abetting the comeback was First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, who with her stylish pillbox hats and boxy jackets helped reinvigorate an appetite for French fashion.

But the war also unleashed economic, cultural and generational shifts that presaged a change in fashion power. GIs returned to attend college, build homes and grow businesses. Women empowered by wartime employment outfitted themselves and their children for a new suburban lifestyle that included PTA meetings and Sunday picnics in the family Buick. The manufacturing sector, which began with the sewing machine’s invention in the 1850s, now revved up in volume to dress a generation.

“Before the war, even into the 1950s, people made their own clothes or clothes for their kids,” said Christina Binkley, a style columnist who covers the fashion industry for the Wall Street Journal. But with the post-war boom in manufacturing, ready-to-wear transformed the landscape, and the hunt was on for an engine of design to drive sales. “You can get really, really rich if you can figure out trend,” she said.

And the trend, after the war, was casual, a relaxation of the old dress code, a celebration of the good life. “After the war, there was a real explosion of casual culture, (outfitting) all the baby boomers,” said Goldstein. Dior’s New Look “may have impacted what ladies wore to lunch,” he added, but “leisurewear, California clothes, kids clothes — Paris couldn’t do that. They had to take that from America.”

Enter the new generation of American fashion powerhouses, many Jewish.

Anne Klein was the first, and a visionary. In 1948, at the age of 25, the New York-born Hannah Golofski launched Junior Sophisticates, creating a new category of clothing in a field that was until then defined as men’s, women’s and children’s. Gearing her designs to a new generation of younger, slimmer girls, she offered a sportier, more casual look. By 1968 she launched her own line, pioneering the concept of mix-and-match separates to a profession that usually sold clothes in matched sets, designing for petite women like herself, again creating a new category of sales.

By then, the field was catching up. Ralph Lauren launched his first Polo store, which made only ties, in 1967. And one year later, Calvin Klein sold his first line of coats and sleeveless dresses to Bonwit Teller.

The Bronx-born Calvin Klein loved structure, and sensuality. He was the first to take mundane items like jeans and underwear and turn them into items of sexy fashion. In 1980, creating a new standard in both fashion and advertising, the 38-year-old designer hired actress Brooke Shields, then 15, to pose in blue jeans, asking viewers, “You want to know what comes between me and my Calvins? Nothing.”

For 30 years he rode atop the fashion world. Shocking the tabloids with a personal life that rocketed between women and men, between drugs and sobriety, Klein turned his personal biography into an international brand. By the time he sold his company to Phillips Van Heusen in 2003, his name was a license for everything from belts to perfumes to jackets, and its cachet is still earning millions. But by then he was a designer out of drive. Perhaps the debts of an undisciplined business took their toll. Or maybe anticipating market trend drained his creativity. “In order to survive in fashion industry, you have to be so on top of zeitgeist,” said Binkley. “It’s almost a sickness, you can’t ever stop thinking about it.”

Five years after CK hit the scene, Diane Von Furstenberg – child of a Holocaust survivor, one-time wife of a prince whose mother was the heiress to the Fiat automobile fortune – introduced a new design with the slogan, “Feel like a woman, wear a dress.”

Born two years after her mother’s liberation from Nazi concentration camps, Diane Simone Michelle Halfin early on adopted her mother’s optimism. During the frigid winters, Lily Nahmias had been forced to walk for days in the snow from camp to camp. So, in true survivor spirit, after the war Lily took her entire reparation check from the German government and spent it on a new sable coat.16“She had been so cold in the camps and she never wanted to be cold again!!” DVF wrote in an e-mail to Moment.

In 1973, in an era of counter-culture experimentation when women tried on pants suits and men sported Nehru jackets, DVF introduced the wrap dress, an unapologetically feminine design. Her genius was to rebel against trend, giving women a dress that made them feel sexy, confident, feminine, and somehow still professional.

Asked to account for the overnight sensation that landed her on the cover of Newsweek, von Furstenberg said, “Women were ready for clothes that let them be both sexy and successful, powerful and practical. No one was really designing clothing that was sculpted to fit a woman’s body and also let her go from day into night with ease. I make clothes that are your friends and that make you feel good so that when you open your closet you smile.”

Now head of the Council of Fashion Designers of America, von Furstenberg – whose wrap dress is now a favorite among a new generation of women — says she feels Jewish but not religious. She observes Yom Kippur, the only Jewish holiday on her calendar, because “I believe in the message of the holiday. For me it is a time of reflection and contemplation…a clean start for the new year.”

For many of the post-war generation of designers, fashion was in their blood, an inheritance of family preoccupation. Donna Karan, creator of DKNY line that is a tribute to urban, sophisticated style, is steeped in fashion credentials. Her mother was a model and her stepfather was a hat-maker. Her father Gabby Faske was also in the business, a tailor who died when she was three years old. At 14, working in a clothes shop, she felt confident enough to advise customers on which outfits would most flatter their figures. She trained at Parsons School of Design, before signing up with Anne Klein. Then in 1974, just after Karan gave birth to her daughter Gabrielle, Anne Klein died at the age of 50, of breast cancer. Executives asked the 26-year-old Karan to complete the collection and later named her chief designer for the Anne Klein line. Her own DKNY line was launched nine years later, complete with a Peter Arnell photo of the New York skyline and its iconic view of the Statue of Liberty. As she once told a journalist, “Ralph owned America, Calvin owned sex, so I decided to own New York.”

Like Karan, Kenneth Cole has family roots in the profession – his father Charlie owned the El Greco shoe manufacturing company. In 1982, the younger Cole set out to preview his own new line of shoes at Market Week at New York’s Hilton Hotel. Just back from a trip to Italy, without funds to pay for a hotel room let alone a showroom, Cole rented a trailer. But the city would only grant parking permits to trailers used in movies, so he changed his company’s name to Kenneth Cole Productions, writing in his application that its purpose was to shoot a full-length film, “The Birth of a Shoe Company.” The story goes that he sold 40,000 pairs of shoes in three days, and did made a movie. Ever since, he has pioneered classy, elegant shoes and clothes, and socially responsible advertising. An early company logo: “What you stand for is more important than what you stand in.”

Isaac Mizrahi was also a child of the business. The youngest child and only son of Zeke and Sarah Mizrahi, he grew up in a tight-knit Syrian Jewish community in New Jersey. His father worked in the garment industry, first as a pattern cutter on Wooster Street and later as a manufacturer of children’s clothes. His mother took her son to the ballet, and to shopping expeditions to the major department stores, teaching him to hunt for quality, showing him the magic of designers like Chanel and Balenciagas. Taking lessons in couture’s attention to detail, Mizrahi decided to bring them down market, partnering first with Target and now with Liz Claiborne to deliver fresh, youthful, even whimsical clothes at a modest price – with fabulous seams.

Openly gay, Mizrahi has said he feels Jewish in his soul but is conflicted by the orthodox belief that homosexuality is wrong. Once, asked about what defines couture, he described in loving detail the way designer clothes are made – the special press of the jacket, the turned head of the sleeve, the way the shoulder pads are inserted. “God,” he said, “is in the tailoring.” Michael Kors, son of the Jewish model Joan Hamburger who was Bar Mitzvahed but does not practice Judaism, would likely agree. Known for his workmanship, the graduate of Parsons who was a regular on Bravo’s Project Runway show is so trendy the New York Times recently said that “young celebrities, society figures and their followers … think of him as a groovy alternative to Oscar de la Renta.”

When Mizrahi burst on the scene in the 1980s, American casual style was all the rage. By the time Mizrahi took his designs down market to Target in 2003, the international economy – along with fashion’s manufacturing base — had gone global. Speeded by Internet connections and fueled by cheap labor in Third World countries, American design was still king, but production had moved to Asia. Pressure to feed the beast mounted, as stores added seasons so their merchandise looked fresh (think “cruise line” and “holiday collections”) and designers were forced to create on a 24/7 cycle. The result is a kind of mania for market trend.

“More clothing comes into the Port of Los Angeles from Asia than any other point on the globe,” said the Journal’s Binkley. “Massive quantities are being made in factories that run 24 hours a day. We’ve added seasons, so stores have new collections every week. Designers want to work for H&M. Some would argue that this benefits the consumer, who gets the clothes quickly. But we are filling landfills.”

Amid the frenzy, a new generation of Jewish designers is making a splash.

Marc Jacobs, fired by Perry Ellis in 1993 for designing a grunge look, is now creative director for Louis Vuitton, and for his own line, where he has made grunge both feminine and profitable.

Zac Posen, who as a child stole yarmulkes from his grandparents’ synagogue to make dresses for dolls, is still dressing dolls, winning praise from clients Natalie Portman, Rihanna, Kate Winslet, Cameron Diaz, Jennifer Lopez and Beyoncé for the feminine aesthetic of his design.

And after decades of Jewish fashion designers appealing to the mainstream, some young designers are going ethnic. Levi Okunov, son of a Hassidic rabbi, just launched The 1929 clothing boutique in Manhattan, where he is displaying gowns dotted with poetry by 13th Century Sufi poet Rumi, translated in English, Yiddish and Arabic.

Against the trend, bucking the globalization and mass audience, is one designer who made her reputation on craftsmanship, the kind of painstaking attention to detail that has been lost in the whirl of Zara edginess.

Just days after Budapest was liberated from the Nazis, Judith Peto, who escaped the concentration camps thanks to a forged Swiss diplomatic pass, met an American soldier named Gerson Leiber. Their courtship, marriage and voyage to America marked a singular moment in fashion history. With his help, in 1963 Judith Leiber launched a line of designer purses that became must-have accessories for celebrities, first ladies and fashionistas. “If the Nazis hadn’t occupied Budapest, I would have become a chemist,” Leiber said in an e-mail interview with Moment. Accepted as a chemistry student by Kings’ College in London in 1939, Peto was forced instead to worked in a Jewish-owned company, and she chose to apprentice to the finest handbag maker in Budapest. But with her father and art collector and her grandmother a hat designer, Leiber mused that perhaps it’s in her family blood after all, “perhaps I inherited a sense of design.”

A new generation of immigrants, most Asian, is now breaking through. Like Jason Wu, who designed First Lady Michelle Obama’s Inaugural Gown, they are bringing energy and an eye for trend. Like the Jews who fueled the garment industry more than a century ago, they see in the clothing business an opportunity for success and acceptance.

“In a way it’s fitting,” said Steele. “Modern American fashion is a reaction formation against being an immigrant. It’s a very competitive field, hard to break into. Now, with our factories moving to China or Vietnam, an uncle in China might help,” just as family ties once aided Jewish immigrants in their journey of clothes as both a trade and a talisman. Their success, said Steele, is “a function of their immigrant story.”